Rent-Seeking and Public Sector Unions

Published:

What role do public sector unions play in determining the local government spending priorities? I discuss a trio of recent papers that shed light on this question. Each explores a different source of monopoly power that allows organized public employees to extract rents in the form of higher wages.

Transfers from Uncle Sam

Suppose a city government finds a dollar bill on the ground (or, equivalently, that they receive an unexpected transfer from the federal government). What will they do? Rather than returning the money to residents in the form of lower taxes, Feiveson (2015) shows that they spend it. Interestingly, how they spend it depends on state laws that govern public sector unions. When unions are strong, the extra cash goes to higher wages for public employees; when they are weak, jurisdictions instead hire more employees and invest in infrastructure.

Feiveson exploits geographic variation in federal transfers due to the allocation formulas in President Nixon’s State and Local Fiscal Assistance Act of 1972. These transfers, which comprised roughly 3% of local budgets each year until 1986, were intended to move spending decisions “closer to the people.” Congressional horse-trading led to a geographically-tiered formula that first allocated funds to state areas, then across county areas within the state, and only then across local governments in the county. The result: two similar cities could receive vastly different amounts of money depending on the state and county that they happened to be in.

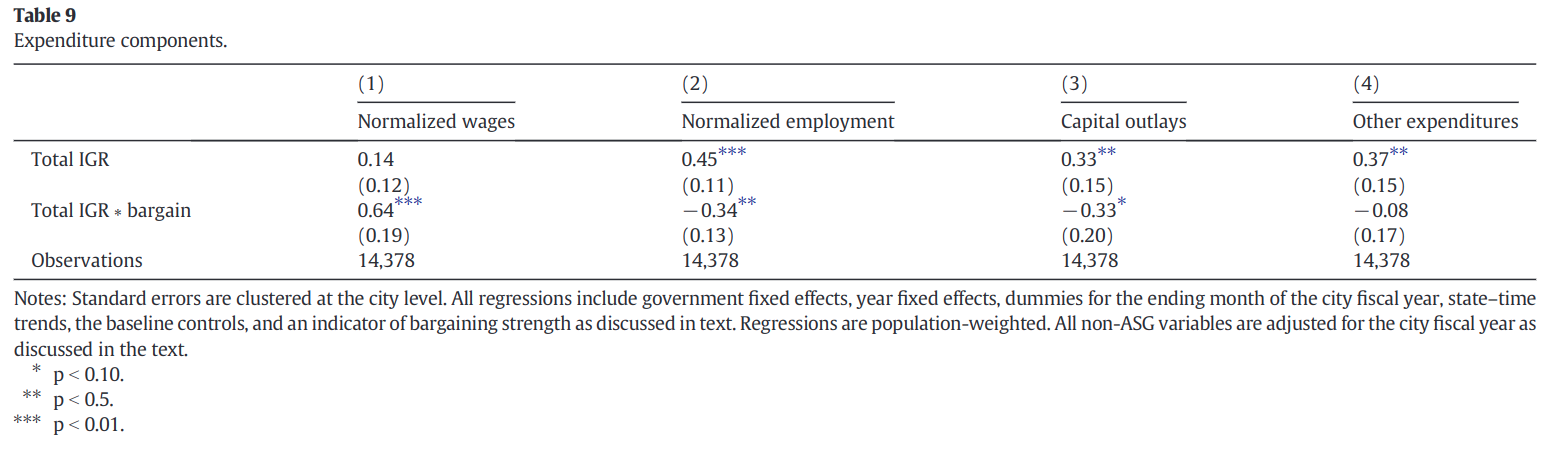

After showing that \$1 of transfers from this program lead to about \$1 of additional spending, Feiveson breaks down spending into four categories: wages, employment, capital outlays, and everything else. She then interacts the amount of federal transfers with an indicator for whether the state requires collective bargaining or not. The key results appear in Table 9 and are copied below:

While cities in pro-union states spend about \$0.78 of the extra dollar on wages, those in anti-union states spend merely \$0.14, with the rest going to employment and capital outlays.

While Feiveson emphasizes the implications of her results for macroeconomic policy and spending multipliers, I think the more interesting lesson is what we learn about the nature of local governments. Cities are sometimes viewed as firms whose shareholders are their residents (hence, a municipal corporation). When firms receive a dollar in windfall profits, we expect them to return it to their shareholders either via dividends or stock buybacks. The fact that cities don’t distribute windfall gains to residents by lowering taxes tells us something about who their true shareholders were in the 1970s: public employees. Whether this is still true today, in the age of remote work and potentially more intense competition among cities for residents, is an open question.

Amenities

A place with great weather, beautiful beaches, or a natural harbor will have some residents even if the local government is corrupt or inefficient. Brueckner and Neumark (2014) push this idea a step further: can public employees actively exploit natural amenities to raise their wages without providing additional services?

In the spirit of Buchanan, Brueckner and Neumark develop a model where public employees control the local government and choose their own wages. In their model, public employees face the same trade-off as any monopolist: to raise more revenue for a raise, they can increase taxes, but that will cause some residents to move elsewhere. Their “wage-maximizing” tax rate will balance higher revenues per resident against the number of residents willing to put up with those taxes. Critically, great amenities allow public employees to push up taxes higher than they could otherwise because some residents will stay for the beaches or sunshine.

Brueckner and Nuemark test this prediction with Mincer-style wage regressions using CPS data. They include the standard demographics controls plus three variables motivated by their model: measures of local amenities, an indicator for public sector status, and their interaction. If public sector workers are able to generate rents from local amenities, this interaction should be positive. In short, nice weather + public employee = higher (relative) wage. And that’s exactly what they find.

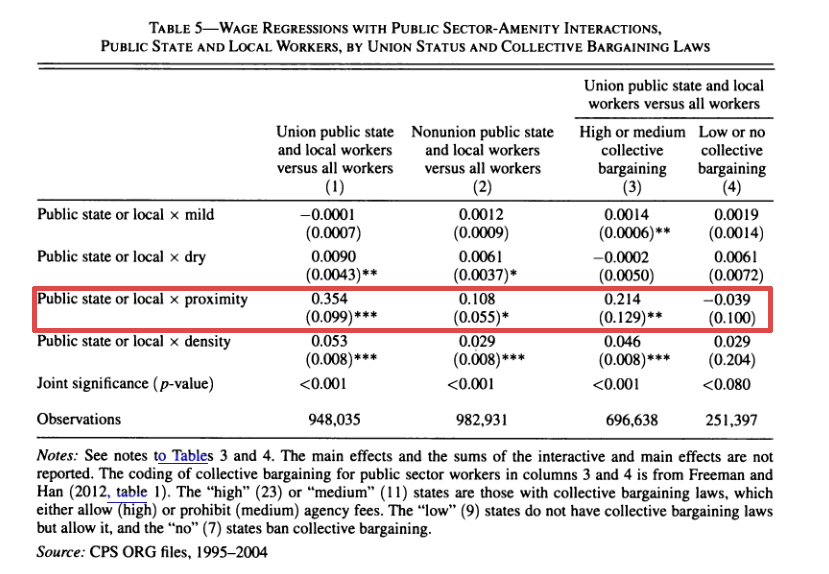

Are all public sector employees able to collect these rents? Not quite. When they split their sample based on the extent of collective bargaining in the state, Brueckner and Neumark find that the effect of amenities on wages is only present in states with strong unions, as seen by comparing columns (3) and (4) in the table below

In the highlighted row, proximity measures how close the average resident of the state is to a beach, Great Lake, or major river. For public employees in states without strong unions, there is little relationship between proximity and wages. But among states with strong unions, moving closer to a body of water is associated with a statistically significant increase in wages.

Inelastic Housing Supply

Diamond (2017) starts from the same intuition as Brueckner and Nuemark, but she focuses on a different source of monopoly power: inelastic housing supply.

Consider two cities, one with shoddy, cheaply-built housing and another with an abundance of high-quality, long-lasting homes. If the first city is hit by a negative shock (like a tax hike without any change to public services), there is little reason for its residents to stick around: their homes would have to be replaced soon anyway, and there’s not much point in building a new house somewhere that no one wants to live. On the other hand, the second city has an inelastic housing supply because its housing is durable: after a negative shock, residents will continue to live there long afterwards simply because their homes are still worth something.

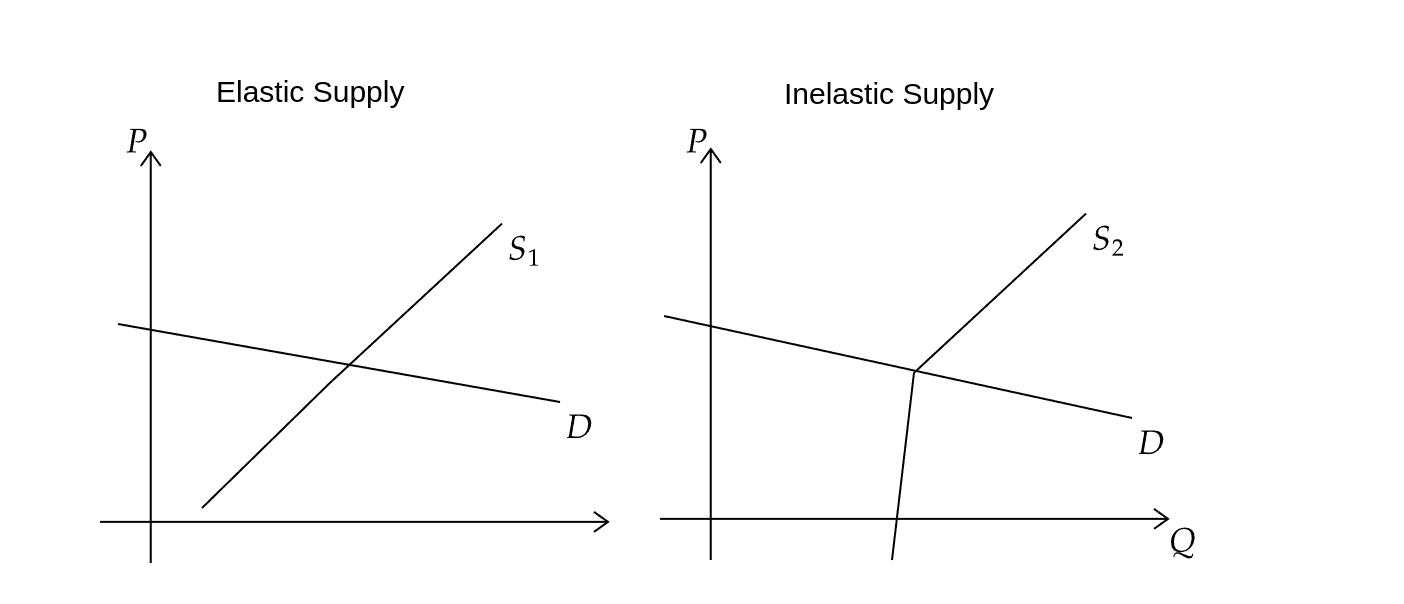

This situation is depicted in the figure below. In the left panel, the city has an elastic housing supply, and the supply adjusts rapidly to changes in price. In the right panel, the city has an inelastic housing supply, and the supply is slow to adjust.

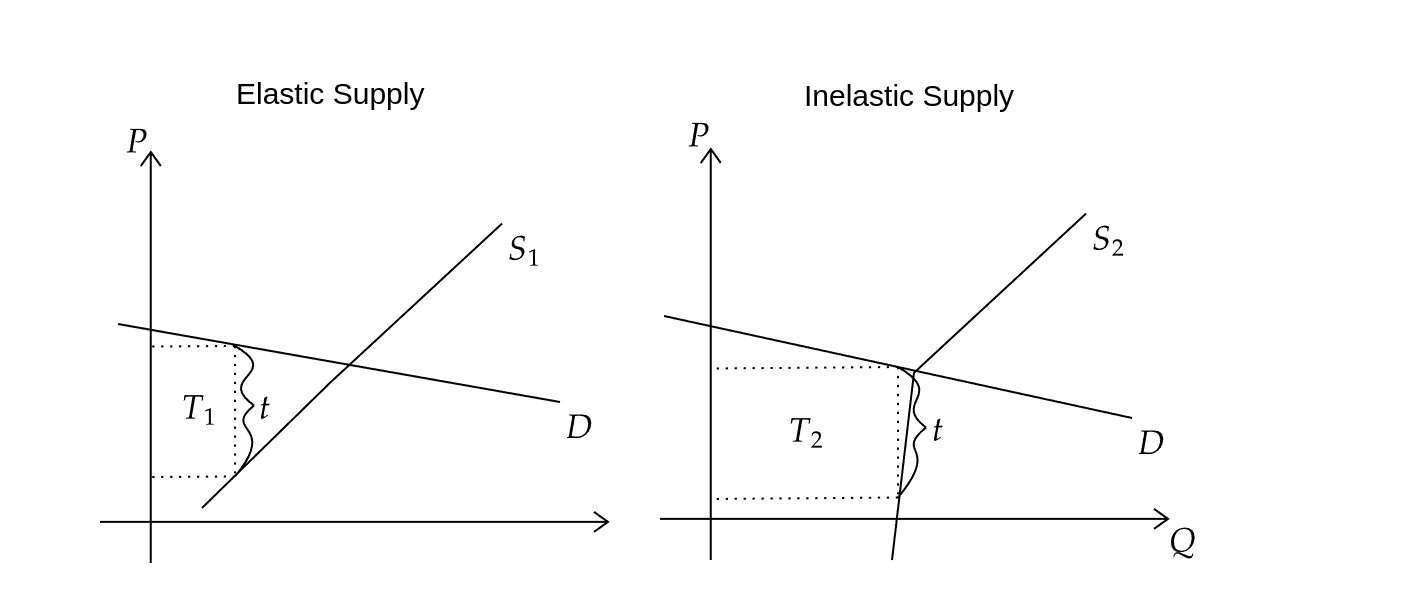

The city with inelastic housing supply can extract more revenue from residents. This is seen in the figure below: after imposing a tax $t$, the inelastic city can raise $T_2$, while the elastic city can only raise $T_1$, and by inspection, $T_2 > T_1$.

Intuitively, residents in the inelastic city are compensated for the tax increase by lower housing rents. Even though taxes are high, they can afford them because their rents are low: someone already paid for their house to be built! In the elastic city, residents would have to pay the tax and pay for someone to build a new house for them, so they simply pack up and leave.

So far, so good. But how do public sector unions fit it here? Diamond repeats the empirical exercise from Bruencker and Neumark, but she replaces their amenities variables with a measure of housing supply elasticity based on the availability of buildable land from Saiz (2010).

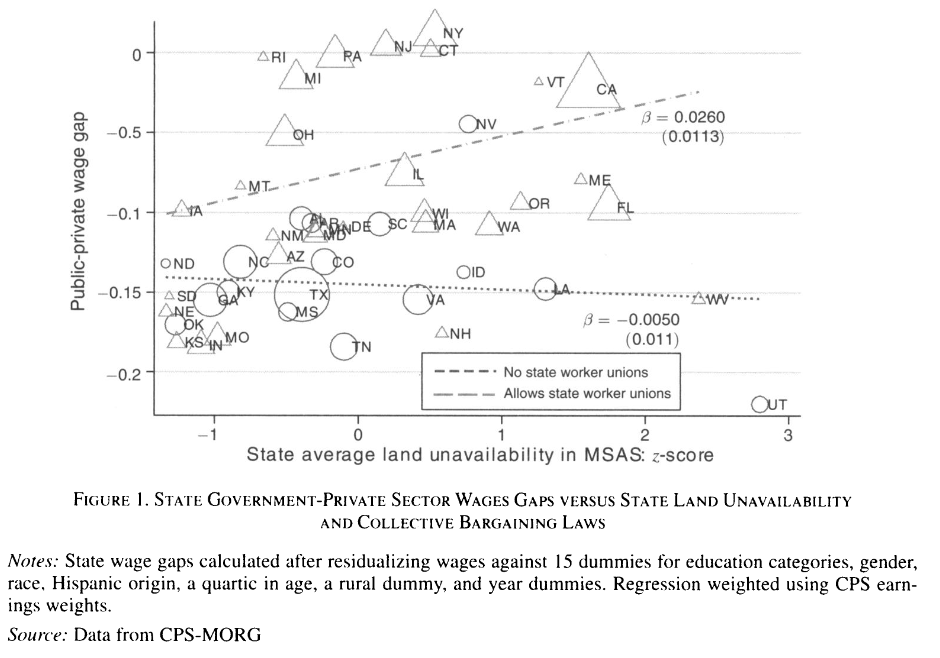

Here, Diamond provides us with a nice graph that I’ve copied below. The x-axis shows a normalized measure of land availability that varies depending on the ruggedness of the terrain and the presence of water. The y-axis depicts the (residualized) wage gap between public and private sector workers.

In states that don’t allow public sector bargaining, the gap between public and private wages is basically the same regardless of the terrain: public workers in both West Virginia and South Dakota earn about 15% less than a comparable private sector worker despite the massively different landscapes.

In states that allow public sector bargaining, however, there’s a strong positive relationship between the two measures. California and Vermont have limited buildable land, and public employees there make only 5% less than private employees, while Iowa and Kansas have ample land and public employees there take a 20% pay cut relative to the private sector.

While this is a striking result, there are some missing pieces to the model. Presumably, land availability should only affect housing supply after positive shocks: no matter whether there is a lake or a corn field next to my house, it will still depreciate at a similar rate. But rent extraction by the public sector would seem to be a negative shock, and hence the relevant part of the supply curve isn’t obviously related to land availability.

Some Parting Thoughts

In each of these studies, government productivity is the elephant in the room. So what if public wages are high – maybe they’ve earned that raise by working harder or longer! There seem to be room for a project that constructed an objective measure of government output. Ideally, something that could be compared across jurisdictions and over time, like wait times at the DMV or 911 response times. Teacher value-added could also work, but I’m not aware of any such estimates that are available for multiple school districts.

Another way to get at public sector productivity is to look at government procurement. If two jurisdictions purchase the same inputs for different prices, it is safe to say that one is operating more efficiently than the other. There’s ongoing research on this topic by Cailinn Slattery in the US and Garcia-Santana and Santamaria (2021) in France and Spain, but I believe these questions are still ripe for exploration.

References

Diamond, Rebecca. “Housing supply elasticity and rent extraction by state and local governments.” American Economic Journal: Economic Policy 9, no. 1 (2017): 74-111. https://doi.org/10.1257/pol.20150320.

Feiveson, Laura. “General revenue sharing and public sector unions.” Journal of Public Economics 125 (2015): 28-45. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jpubeco.2015.03.004.

Brueckner, Jan K., and David Neumark. “Beaches, sunshine, and public sector pay: theory and evidence on amenities and rent extraction by government workers.” American Economic Journal: Economic Policy 6, no. 2 (2014): 198-230. http://dx.doi.org/10.1257/pol.6.2.198.

Garcıa-Santana, Manuel, and Marta Santamarıa. “Border Effects in Public procurement: the Aggregate Effects of Governments’ Home Bias.” (2021). Working paper.