The New Dynamics of Fiscal Federalism

May 27, 2025

Revisiting Oates After Five Decades

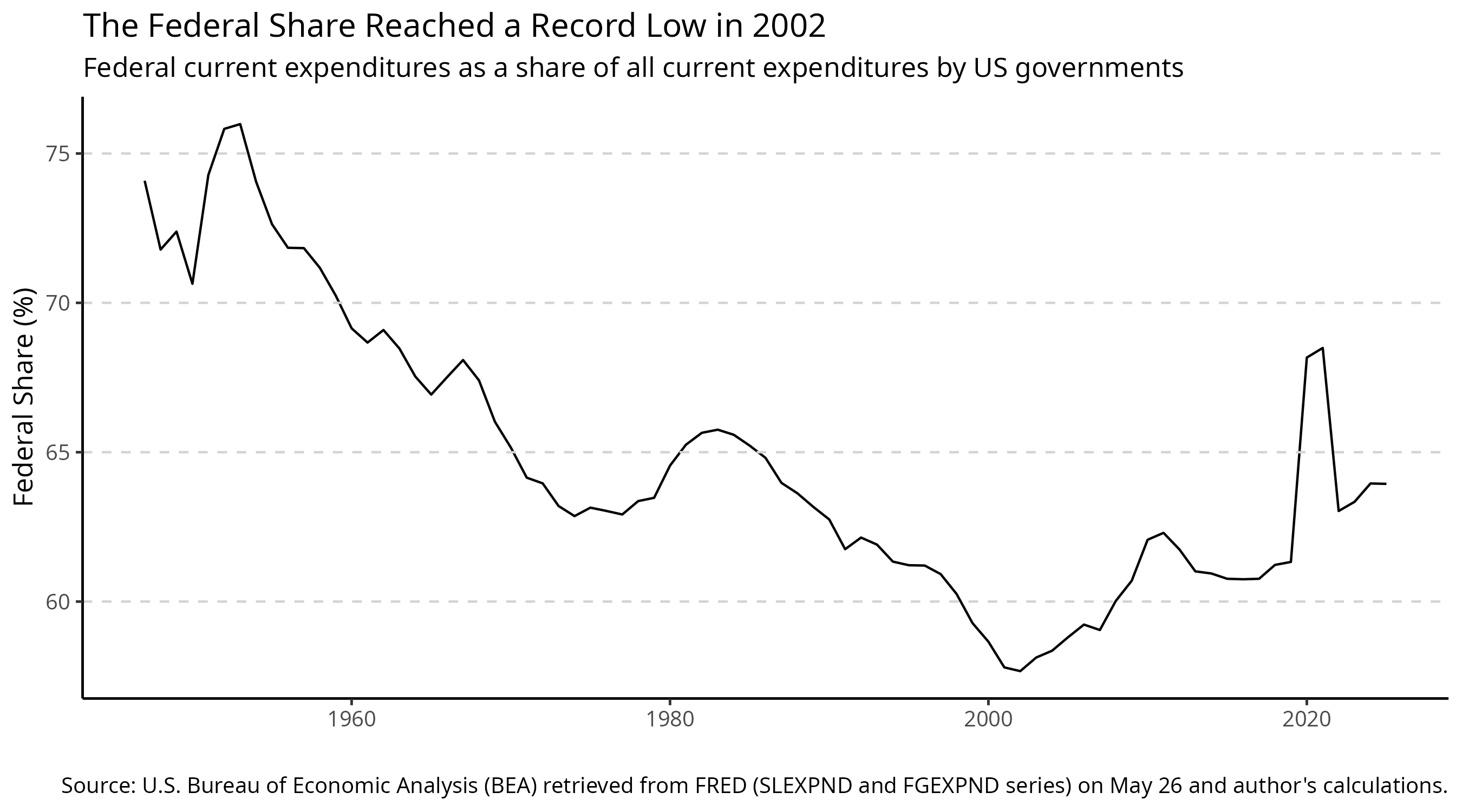

The federal share of all government spending has inched up steadily since 2002. This shift has concrete implications: when spending decisions are made by Congress, rather than by local politicians, then communities may get roads they don’t prioritize rather than the parks or schools that they prefer.

When is more or less centralization optimal? Wallace Oates’ seminal 1972 work on fiscal federalism lays out the relevant economics.Oates, Wallace E. Fiscal Federalism. Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1972. Decentralized provision of public goods generates efficiency gains under two conditions: when households have heterogeneous preferences over public goods; and when households are sorted geographically on the basis of those preferences. In the absence of spillovers and economies of scale, his “decentralization theorem” shows that variable and decentralized provision dominates uniform central provision.

After gradually declining for three decades, the federal government’s share of current spending (excluding transfer and interest) began to inch upwards steadily in 2002. The share is now at its highest level since 1988.This increase is not caused by rising spending on entitlement programs: transfer payments are not counted as production and are therefore excluded from the NIPA measures of consumption expenditures. Intergovernmental transfers and interest payments are also excluded. “Chapter 9: Government Consumption Expenditures and Gross Investment.” NIPA Handbook. Bureau of Economic Analysis, December 2024. https://www.bea.gov/resources/methodologies/nipa-handbook/pdf/.

Is a larger federal share economically efficient? Oates viewed labor mobility and sorting as the key drivers of gains from decentralization. I revisit these fundamentals and ask if they’ve changed since 2002 in a way that would justify a rising federal share.

Labor Mobility and Sorting

Labor mobility is likely to increase the efficiency gains from decentralization. When households “vote with their feet” and sort themselves into jurisdictions that match their preferences for public goods, there will be a closer alignment between the provision of public goods and the residents’ preferences. Consider the likely difference in demand for green energy between California and Oklahoma, or the different preferences for clean public spaces among New Yorkers and retirees in Florida.

Internal migration rates in the US have declined over time. These declines are pervasive across demographic groups and household types and appear to be driven by two forces: an aging population and an increased attachment to one’s place of origin.Mangum, Kyle, and Patrick Coate. “Fast locations and slowing labor mobility.” (2019). https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3843805. Declining mobility suggests that households may be less likely to move to jurisdictions with their preferred level of public goods, reducing the efficiency gains from decentralization.

However, one reason households may be less likely to move is that they already live in their preferred location. Indeed, between 1980 and 2017 individuals have become increasingly segregated by education.Diamond, Rebecca, and Cecile Gaubert. “Spatial Sorting and Inequality.” Annual Review of Economics 14, no. 1 (2022): 795–819. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-economics-051420-110839. Greater segregation by education suggests higher efficiency gains from decentralization, indicating that the recently increased federal share is unlikely to improve the efficiency of public goods provision. This is the central puzzle: Americans are more sorted by preferences than they were in 2002, yet the federal government is claiming a larger share of public goods provision. The Oates framework suggests this is backwards.

Factor Mobility

Mobile capital presents a challenge for subnational governments. If localities cannot impose a pure benefit tax, perhaps because of legal or technological constraints, then they will struggle to finance public goods without causing distortions in capital and labor markets. This “flight to the bottom” problem has drawn particular attention in the context of corporate taxation, where local governments compete to attract businesses through subsidies or low tax rates.Slattery, Cailin. “Bidding for Firms: Subsidy Competition in the U.S.” (April 23, 2024). Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3250356.

A second challenge is that factor mobility enlarges the scope for spillovers across jurisdictions. If households are highly mobile, then children educated in one jurisdiction will often work elsewhere, providing benefits to other jurisdictions through their human capital.Of course, this is not a concern if parents fully internalize the benefits of their children’s education and are willing to finance it through local taxes. Similarly, start-ups that incubate in San Francisco may move to Austin or New York, reducing the returns to local public goods that support innovation.

While changes in capital mobility could motivate a larger federal share of spending to reduce tax competition and internalize fiscal externalities, I am not aware of any evidence that capital mobility inside the US has changed significantly in the past two decades. On the whole, then, increased sorting since 2000 suggests the federal share of spending ought to be smaller, not larger.

Crises and Federal Capacity

Federal governments tend to take on additional responsibilities during national crises. This pattern has played out repeatedly in US history, most obviously during the Great Depression and World War II, but also in recent years during the Great Recession and COVID-19 pandemic. The step-up in the federal share during the latter two is clearly visible on the figure. However, while such crises may justify a level change in the federal share that sticks long after its original motivation, it is not clear why a crisis would cause a sustained increase.

The Future of Federalism

Federalism has few friends in national politics.Nagourney, Adam. “Trump’s Power Grab Defies G.O.P. Orthodoxy on Local Control.” The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2025/02/07/us/politics/donald-trump-california-newyork-executive-orders.html. While budgetary pressures from rising entitlement spending and interest payments are likely to divert some federal resources away from current expenditures, they will also depress intergovernmental transfersSanger-Katz, Margot and Sarah Kliff. “G.O.P. Targets a Medicaid Loophole Used by 49 States to Grab Federal Money.” The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2025/05/06/upshot/medicaid-hospitals-republicans-cuts.html. and increase demands on taxpayers in high-tax cities, reducing the ability of local governments to finance their own public goods.

The steady increase in federal expenditure share since 2002 appears to reflect gradual policy drift that is unsupported by changes in underlying economic fundamentals. In an era of increased flexibility due to remote work and substantial scope for policy experimentation using AI to evaluate local policy, offering more local control over public goods provision could yield large efficiency gains by better matching public goods to local preferences. One promising policy in this direction is California’s recent Outcome Reviews program, a structured effort to evaluate whether state programs are achieving their intended outcomes.See Jennifer Pahkla. “Outcomes Review: Realigning Legislative Incentives” Eating Policy. Substack. https://www.eatingpolicy.com/p/outcomes-reviews-realigning-legislative. As the cost of program evaluation falls due to better public datasets and AI researchers, there may be increasing gains to decentralization and experimentation.

Appendix: How Should We Measure Centralization?

The traditional Oates framework assumes a clean division of labor: local governments provide locally-consumed public goods, while the federal government provides uniform national public goods. This assumption underlies the use of federal expenditure share as a measure of centralization. However, American governance has never fit this tidy model, and the mismatch has grown more pronounced over time.Even in 1972, Oates recognized this tension, worrying that “economic theory is becoming increasingly irrelevant to the problems of fiscal federalism.”

The federal government has long been in the business of place-based policy. On the spending side, it channels federal money to particular locations through grants (like the Community Development Block Grant), infrastructure projects (like the Interstate Highway System), and education (through community colleges and universities).Hanson, Gordon H., Dani Rodrik, and Rohan Sandhu. “The U.S. Place-Based Policy Supply Chain.” Working Paper. Working Paper Series. National Bureau of Economic Research, February 2025. https://doi.org/10.3386/w33511. On the tax side, the progressive income tax effectively imposes a higher tax burden on households in highly productive or unattractive locationsAlbouy, David. “The unequal geographic burden of federal taxation.” Journal of Political Economy 117, no. 4 (2009): 635-667., and the SALT deduction has a large effect on the net-of-tax price of local public goods in high-tax states.Ambrose, Brent W., and Maxence Valentin. “Federal tax deductions and the demand for local public goods.” Review of Economics and Statistics (2024): 1-39.

This complexity raises a fundamental question: Does the federal expenditure share meaningfully capture centralization trends? There are two good reasons to put some stock in the federal share as a benchmark, but they come with important caveats.

First, even when federal spending is geographically targeted, it often reflects federal rather than local priorities. Federal infrastructure grants may build transit systems that communities wouldn’t have funded themselves while neglecting the parks or schools they actually prefer. This substitution of federal for local judgment is precisely what the centralization concern captures.

Second, if federal place-based spending is roughly constant, we can still learn something from changes in the federal share. Place-based federal policy affects the level of federal current spending, not the trend, so a rising federal share indicates a shift towards centralization.

Tags: public finance, fiscal federalism